Styleforum is old school. Not necessarily in the sartorial sense, but because it is fundamentally an artifact of an earlier internet: an online message board -- a visually mundane community of interest, by and for drilled-down dorks, fostering extended discussions of hardcore esoterica. In an online world dominated by the evanescent buzz of social media, there’s something a bit anachronistic about Styleforum’s underlying conceit: that the essential commodity of men’s style isn’t image, or inspiration, but information -- freely shared, carefully parsed, hotly debated, and densely archived in a process more socially mediated than likes, retweets, favorites, and pins can ever provide.

My stepfather’s wardrobe, mainly assembled in the 1980s, was typical for a businessman of his era, filled with mini herringbone, baby houndstooth, faint pinstripes, and muted glen plaids, all rendered in clear-finished worsted. In the immediately post-Herb Tarlek era, subtlety was a byword for taste -- a vaguely Reaganite reaction against the seizure-inducing liberties of pattern taken by 1970s permanent press. Suits like my stepfather’s were the bland, joyless, semi-solid uniforms (often framing the brittle rictus of a “fun” necktie) that augured the end of the tailored era, and to this day they fill the mournful racks of thrift stores and various other men’s warehouses nationwide.

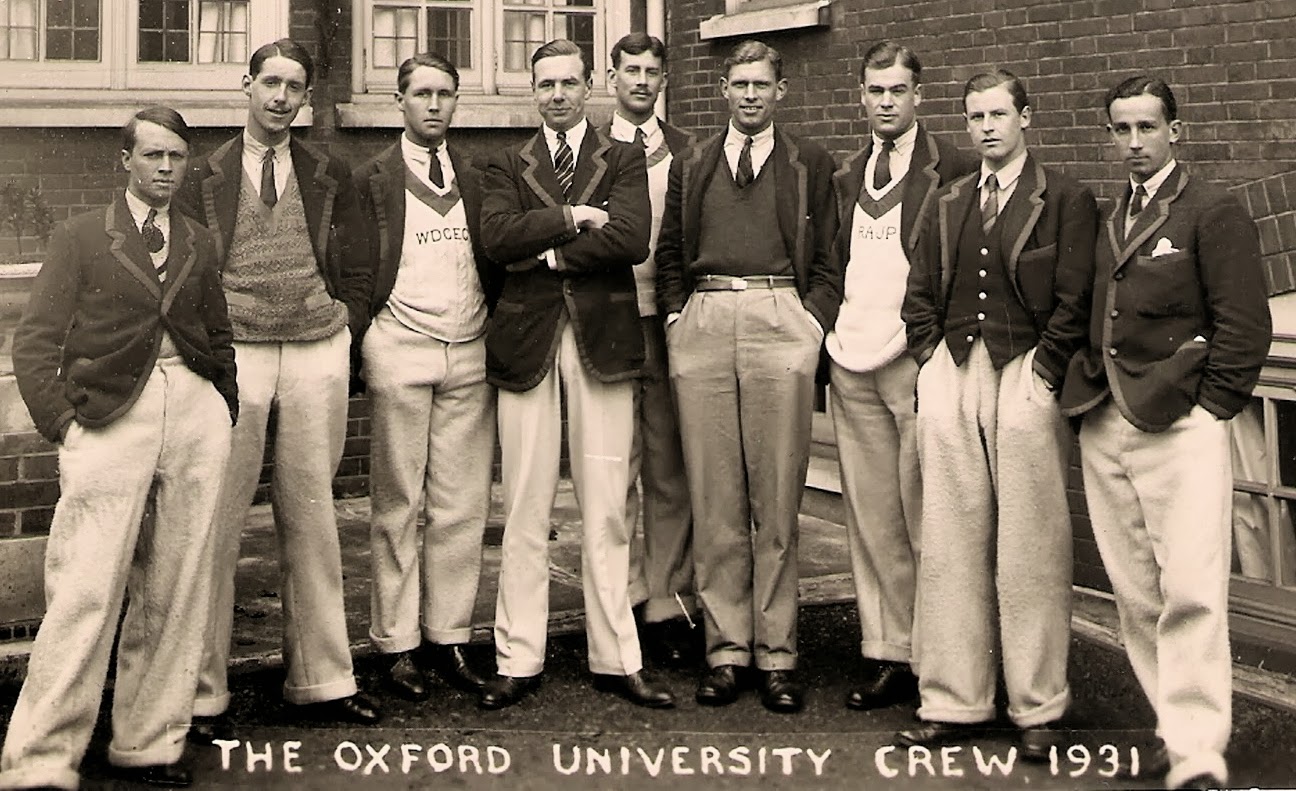

Clothes are inherently, gloriously transformational. They have always been a means -- particularly for those without many means -- to punch above one’s weight, to jump tracks to a different life. This is of course why they’ve been so closely regulated throughout history, subject to review by ecclesiastic authorities for decency, sumptuary laws for impudence, fashion editors for taste -- all efforts to restrict the potentially dangerous power of clothes, to reserve it for elites, be they medieval royalty, industrial aristocracy, Oxbridge/Ivy undergraduates, or simply the cool kids at school.

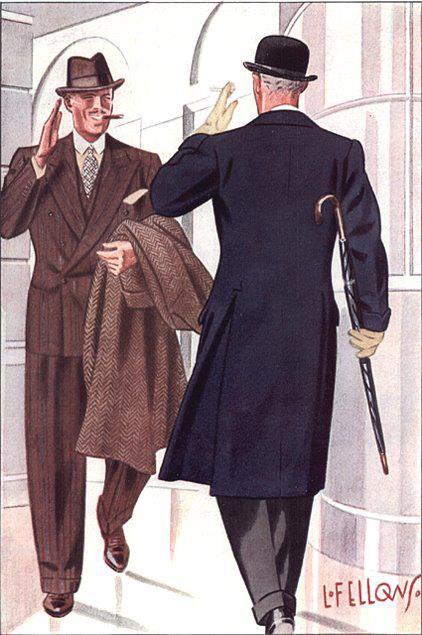

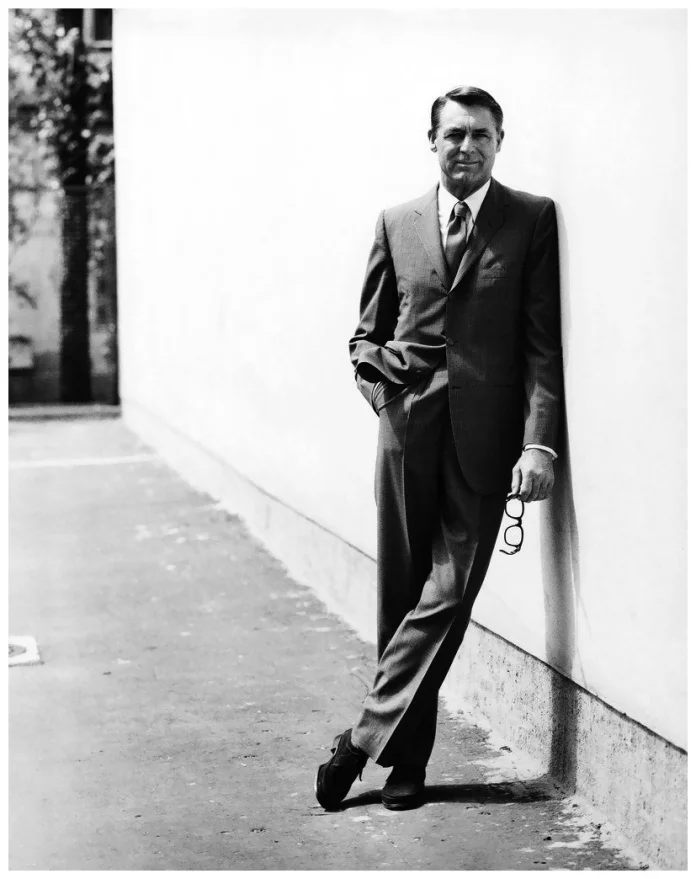

You can spot a truly excellent suit at a hundred paces. There’s something in the quicksilver silhouette of good cloth, well-cut and shaped over a shifting body, nowhere tight or loose, that’s unmistakable even at range. It’s all the more apparent without the distraction of superficial embellishments, which are always seeking to draw attention to themselves, however discreetly: handsewn buttonholes, surgeon’s cuffs, pickstitching. Good clothes are never really about these details. As with a fine watch, the real art of classical dressing lies not in individual elements, but in their movement -- their integration of complex elements to produce a single, simple effect: time and timelessness, respectively.

I suspect there comes a time for many a recreational dresser when he surveys his classically balanced wardrobe of suits, sportcoats, odd trousers, shirts, knits, neckwear, shoes, outerwear, hats, and accessories, and feels a slight pang of existential anxiety. It is at this point that he usually invests in a tuxedo, but this only delays the inevitable reckoning: Is this all there is? Is there nothing more? Here, surely, one should start saving in earnest for the higher education of one’s offspring, but chances are that there remains a final frontier of finery to explore, a last sartorial summit to climb, one more herd of haberdashery to hunt. I speak, of course, of loungewear.

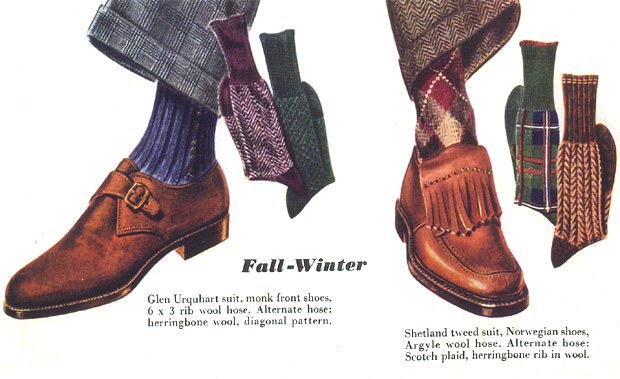

A few years ago, the New York Times observed that resolutely unstyled Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and their acolytes were indulging in fancy novelty socks. These mildly transgressive flashes of bright color and bold pattern appeared to suggest a bat-squeak of sartorial awareness among the be-hoodied without compromising their geek-cred with the slightest whiff of fashion victimhood. While some of these men could indeed purchase Savile Row outright, their garish hose were tokens not of oligarchical bombast, but rather of hip whimsy. Enabled by a proliferation of savvy online retailers and sock-of-the-month clubs (certain of which remove the hassle of actual selection), it was a perfect storm of a mass trend. Like the contemporaneously ascendant pocket square, a good pair of eye-catching socks could easily and inexpensively add a dash of derring-do to one’s otherwise drab attire. Steez for straight dudes in straightened times, if you please.

Sartorially speaking, summer is loud in a crowd, all stark contrast and bright colors, reflecting the glare and shadow of hard midday sun and the plastic glow of pools and popsicles. Autumn, on the other hand, is a solitary early evening stroll through long golden light, dry leaves rustling on crisp woodsmoked breezes into soft flannel cuffs. Sentimental? You bet your ass. Dressers tend to be an earnest lot, and we live for this stuff. Traditionally, good dressing was largely an art of organically harmonizing with one’s environment, gamely playing a small role in holistic tableaus of town and country. In no other season is such a genteel conceit still so pleasantly plausible.

One of the great pleasures of the autumnal wardrobe flip is not only rediscovering heavier clothes, but the sundry seasonal accessories that accompany them. My personal favorites are found in the glove bin. Too often regarded as objects of mundane necessity, well-made gloves can be, like hats, essential sartorial punctuation -- final flourishes that can really take one’s presentation from the elegant to the extraordinary. Aside from shoes, belts, and watchbands, gloves are the only occasion for leather in a classic wardrobe, and certainly the most sensuous. The elemental simplicity of the finest unlined gloves -- just skin and thread, maybe a pearl button -- make it easy to admire the craftsmanship of hand-cutting and stitching, particularly since they’re bound to spend so much time on your hands or in them, readily available on endless occasions to be elegantly held, fiddled with, put back on, and taken off again.

As dressers throughout the northern hemisphere eye their Harris tweeds and heavy flannels impatiently, we’ve already entered the long season for one of the most unique, interesting, and underappreciated cool weather fabrics that should be -- and isn’t -- in every man’s wardrobe: loden. It’s not necessarily what you’re thinking. My own favorite loden garment is a buttery soft, unlined zephyr-weight topcoat in a warm dove gray, lighter than any raincoat and almost as good in an early autumn drizzle. But I like the classic, heavy, iconically evergreen Mitterleuropäisch stuff too.

The first cold rain of autumn is falling. It’s the kind of dark grey early September morning that has never stopped reminding me of sad little marches to elementary school, the last long shadows of summer having given way to the harsh fluorescence of overheated classrooms. I took what solace I could from puddle-jumping in a stout pair of rubber boots and a vinyl raincoat, clammy yet cozy, wonderfully impervious. Like most boys, as I grew older I eschewed these very sensible items, along with the maternal diligence they implied, walking Cool in wet clothes and squishy shoes.

Formal eveningwear is the last bastion of die-hard sartorial pedantry. For well over a century, it has been technically defined as a single platonic form: the immutable tailcoat ensemble, negotiable only in the cut of the waistcoat. Contemporary convention has of course promoted the semi-formal tuxedo* to be the gussiest gear most of us will ever don, but even here, acceptable variation is limited to a handful of styles -- single button or double-breasted, peaked or shawl lapels -- and two colors: black or midnight blue. But as it is now, must it ever be, world without end? Having myself recently joined the small band of miscreants who possess brown tuxedos, I will now attempt to use this modest platform to justify them. Bear with me.

I was asked recently if I thought dressing was an art like painting, or an art like flower arrangement. It’s a good question, and one that can be answered either way by different folks equally passionate about clothes, but I didn’t hesitate before responding. To me, the act of putting good clothes on well is roundly analogous with flower arranging, particularly in its minimalist ikebana incarnation: less an art of exalted creation than refined presentation. Both require a keen eye for found elements, reflect states of mind rather than points of view, and reward restraint. Neither, frankly, is rocket science.

Bloggers can go on all we like about the “menswear renaissance,” but the fact of the matter is that even in a sartorial capital like New York, truly well-dressed men remain thin on the ground. One can certainly find any number of suits shuttling between the money mines of Wall Street and Midtown, but theirs are overwhelmingly joyless ensembles: worsted work uniforms worn with thick dull shoes, indifferent ties indifferently knotted, and slung laptop bags biting deep into overpadded shoulders. It’s not passing judgment to observe that these guys would rather be wearing something else.

The time for wearing summer togs grows shorter with the days. Whether or not you strictly observe arbitrary rules of propriety, recreational dressers define seasons with seasonal clothing, and Labor Day is the time to start furling the Nantucket reds, tennis whites, and marine blues of high summer. For most of us, this comes not a moment too soon: the bloom has long been off the roses of bold summer color, and we crave the leafier palette of fall. Only the most delusionally eager Anglophiles will be brushing down their flannel and tweed anytime soon, however. This is America, after all, and this is the 21st century -- you’d be lucky to need that stuff for another couple months. Indian summer awaits.

Commonly worn by men in Latin America, Zimbabwe, the Philippines, Hispanic communities in the United States, and the politicians pandering to them, the humble guayabera is a global staple of hot weather attire. Complete with an apocryphal origin story (peasants’ pockets for guava portage? Please.) and tempered by decades of ossified styling, it has earned its unique place in the menswear canon.

There’s a certain masochism in most classic dressers’ stubborn adherence to tailored clothing as the mercury rises and the humidity settles in. We justify having distinct seasonal wardrobes with satisfyingly technical appraisals of weight and weave, making a nuanced science of dressing for the weather. I can’t help but wonder, however, if the “practical” dimension of classic summer attire isn’t suffused with a romance all its own, based on quaint and somewhat delusional notions of how effectively gentlemen keep their cool.

There is perhaps no more contemptible species to an Oxford undergraduate than an American doing a Junior Year Abroad in semi-precious dress suggesting one too many Merchant-Ivory viewings. For most native students, the City of the Dreaming Spires is first and foremost simply College (or “Uni” in the native vernacular), their first taste of independence -- all subsidized beer, kebab vans, and midnight oil -- and rightly so. But having already cut my collegiate teeth back in the States, I had come for a different education, preferring to concentrate on the grand subject rendered all around me in Cotswold stone and a mythos of youthful languor.

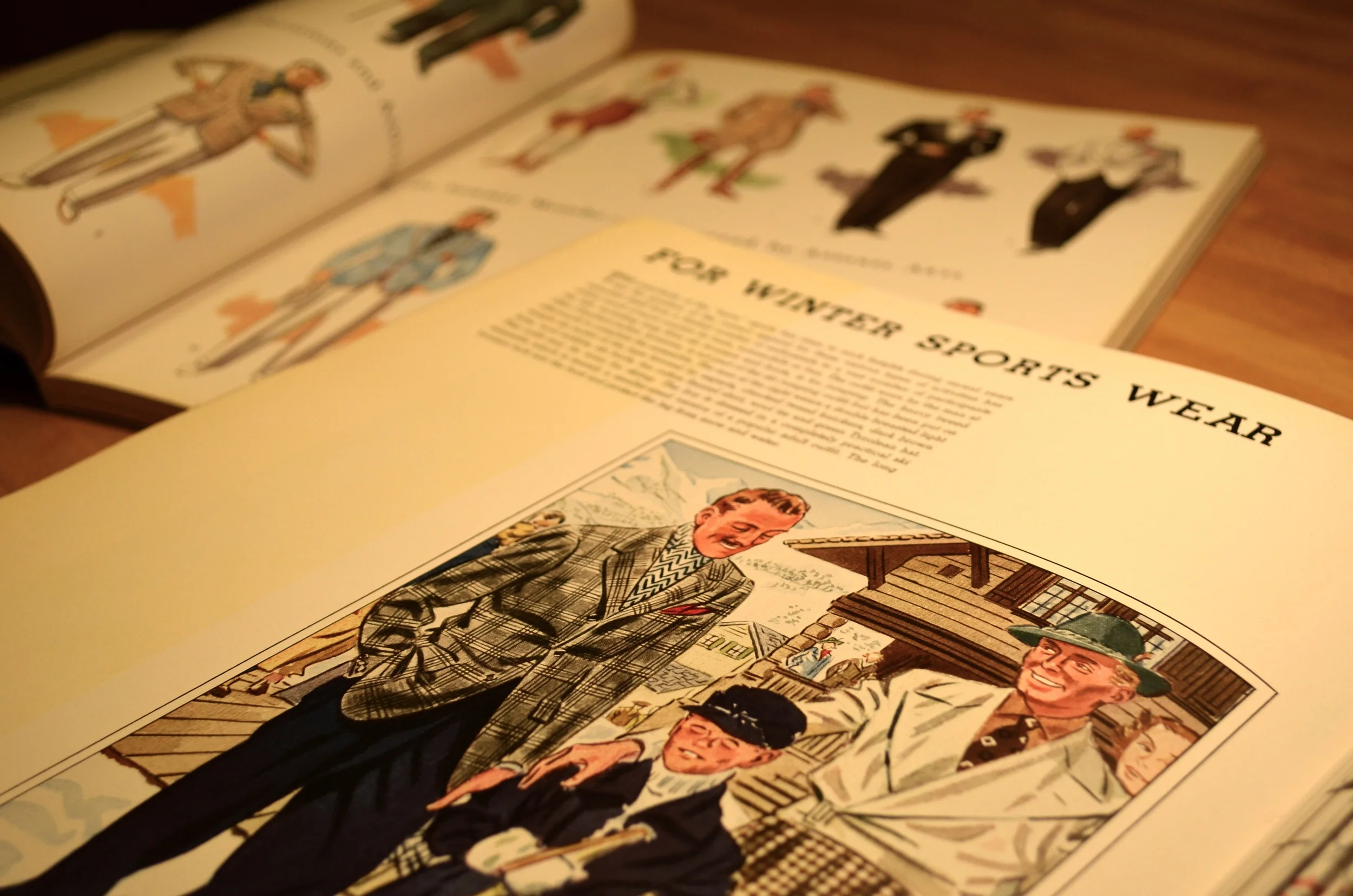

Fashion, in its pure and ideal form, is no more or less than a sartorial reflection of its times, and as such is nothing to be ashamed or contemptuous of. It has, of course, become something quite different over recent decades, as the “fashion industry” has supplanted the clothing trade. The latter is what sponsored Apparel Arts, with advertisements offering dense summaries of any given product’s exquisitely tasteful details, or touting the latest wonder technology which gave it superior comfort or fit. The fashion industry, on the other hand, is primarily in the business of manufacturing image and yearning -- as fleeting and insubstantial as the fragrances which gird its bottom line, and for which actual clothing has only ever been a token.

Whether a splash of flashy color, a sliver of crisp linen, or a puff of dusty ancient madder, there is no surer indicator of a man’s pleasure in dressing than the presence of a pocket square. Being fundamentally unnecessary renders them a bit defiant, bespeaking an aspiration to elegance above and beyond the call. There are few rules to wearing them, and fewer still that should never be broken, but like most men who’ve been recreationally dressing either too long or not long enough, I have my finely-grained and highly-held opinions on the subject.

Let us praise the Hollywood waisted trouser. Derived from classic English brace-tops, improved with the addition of side adjusters or dropped belt loops, and made famous by American matinee idols on and off the screen through the 1950s, their distinguishing characteristic is having no waistband, relying instead on pleats, darts, and seams around the hips to define an elegant taper to the natural waist. When cut and fit properly, this construction is not only visually sleek, but extremely comfortable, with the weight of the garment distributed evenly across the hips rather than cinched at the waist -- rather like how well-cut shoulders render a coat weightless on the back. These are the trousers Astaire famously belted with a necktie, and which Sinatra never quite filled out onstage with the Dorseys.

At its most basic level, taste in attire is often defined by its absence. Tastelessness is no more or less than a lack of respect or appreciation for context. It knows no material manifestation, only awkward occasions: T-shirts at the opera, oxfords at the beach. To have good taste in clothes is fundamentally to have sound, worldly, well-adjusted judgment -- happy, if not eager, to please. It signals belonging to something worth belonging to. (There is of course another definition of taste -- preference -- but that way lies relativism, “lifestyle,” and death; let’s presume that anyone reading this is already a stout advocate of tailored clothing, and focus on what really cuts the mustard in that department.)

The phrase “dressing for the occasion” sounds a bit starchy these days, conjuring the sartorial arms race initiated by Victorian aristocrats to distinguish themselves from the merely wealthy. For all their fascinating and telegenic detail, those talcum-grained distinctions of appropriate dress are now, of course, totally ridiculous. While I’ve probably done a bit of “Half Mourning” myself, its formal sartorial distinction from “Ordinary Mourning” is well off the crazy cliff, and may it rest in peace. Nor should we embrace somewhat less hoary anachronisms like “no brown in town” and “no white before Memorial Day.” Such dictates are fun to know and observe within reason, but their real utility lies not in avoiding archaic faux paux, but in understanding the aesthetic principles behind them (e.g. earth tones are inherently less formal than the charcoals and navies which traditionally constitute business attire, and white looks less brazen on bright sunny days).

Virtually all Americans born since the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (not to mention their Baby Boomer parents) have the daily ritual etched onto their first, best souls. A clean-cut, slightly stooped man -- never young but never quite old -- enters a modest living room and greets his Television Neighbors with a smile and a gentle song as he swaps out his workaday coat and hard-soled loafers for a friendly zippered cardigan and blue canvas sneakers. Despite having one of those iconic sweaters (hand-knit by his mother!) on permanent display in the Smithsonian, Fred Rogers would probably not have held himself up as a sartorial exemplar, but having now rewatched the entire series curled up with my four-year-old daughter, I realize that’s exactly what he is.

Clever company has always reviled nostalgia as sentimental at best, reactionary at worst -- the antithesis of the modern, the progressive, the original, the new. Of course, the whole notion of modernity is a bit outdated these days: for better and for worse, our Here and Now is a whole lot of This and That, Once Upon a Time. The internet has made the past an unprecedentedly vital part of the cultural present, a roiling synthesis of styles and traditions from which individuals are free to cull their identities not according to who they are, strictly speaking, but who they wish to be. “Authenticity” -- that Holy Grail of contemporary Arts & Leisure -- is now less an embodied quality than a principled intention: to live beyond irony.

If fine men’s clothes have a spiritual home, it’s England. It was there that coarse country cloth was first tamed by exquisite urban cut, giving birth to the modern suit and inspiring generations of dandies to study the rich lore of tweed and flannel. My own rather fuzzy wardrobe certainly testifies to a deep and abiding Anglophilia, enabled by New York City’s crisp autumns, frigid winters, and damp springs. The ubiquitous Stars and Stripes of Memorial Day, however, usher in a sartorial season as distinctly American as grilled hot dogs.

There’s something profoundly organic about the way proper care revives good clothes. Wrinkles fall out with steam. Cremes nourish dry old shoes, with wax burnishing their rough scars into smooth depth. Anyone who’s ever pressed his own shirts knows that very specific satisfaction of crisp, fresh renewal. I may not be entirely sure that brushing down a coat accomplishes much, but like brushing my teeth, I do it daily - a modest offering of time at the altar of longevity. Dandies have made high religion of perfecting these rituals with country washing and champagne glacage, but it’s perhaps a bit more balanced to regard them as the small virtues of a sartorial Tao, meditations on maintenance in the face of entropy.

The first film to win the “Big Five” Oscar awards -- Best Picture, Actor, Actress, Director, and Screenplay -- It Happened One Night [1934] actually happens over several nights of a bus, automobile, and shoe leather journey from Miami to New York, undertaken by Clark Gable’s hard-boiled newshound Peter Warne and his journalistic quarry Ellie Andrews -- a runaway heiress played with iconic pluck by Claudette Colbert. This is the movie everyone knows for having collapsed undershirt futures when Warne undresses to reveal a bare chest, but its real sartorial significance lies not in what Gable doesn’t wear, but in everything else he does. His attire throughout the film is a case study in the form and function of classic menswear, not least because the film was a commercial blockbuster, doing much to set the style for a decade that’s set the style ever since.